-

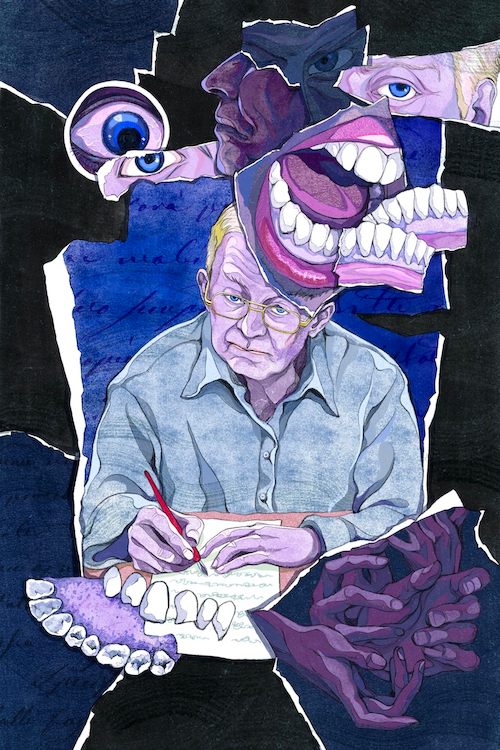

The Tale of Clancy the Scrivener

My new story, The Tale of Clancy the Scrivener, is up on Tor.com. It was edited by the amazing Ann Vandermeer.

The world in which it’s set — an alternate future where sudden, spontaneous, inexplicable mutations burned through the human race, making monsters of nearly everyone it touched — has been percolating in the back of my mind for years. It was the setting of the first story I sold (Creature), though I didn’t know it at the time.

I’ve tried to find various ways back into that world over the years, all to no avail — until I found Clancy, and the little girl whose friendship gives new meaning to his long, fraught life.

-

Knowledge Or Certainty

This clip, from the British documentary The Ascent of Man, is one of the most convincing arguments for the scientific method I’ve ever seen. Scientific inquiry is made of people, which means it’s inherently flawed — but it’s the best tool we’ve found, in our long search for truth, to overcome our tragic shortcomings. Science is the opposite of dogma.

Science is a tribute to what we can know although we are fallible. In the end, the words were said by Oliver Cromwell: ‘I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken.’”

We have to cure ourselves of the itch for absolute knowledge and power. We have to close the distance between the push-button order and the human act. We have to touch people.

-

Cigarettes and Coffee Q&A

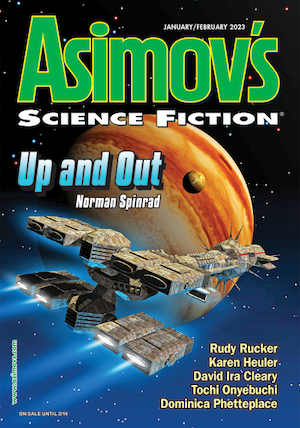

I recently did an online interview with Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine: Asimov’s Q&A.

It’s about my story, Cigarettes and Coffee — which appears in their latest issue — and about writing stuff in general.

Here’s an excerpt:

What is your process?

I don’t have much of a process: it’s more of a practice, and even calling it that probably gives it more credit than it deserves. It boils down to two things:

- Try to show up and write more days than I don’t. The best stuff arrives unexpectedly, not as bolts of inspiration, but as slow insights that grow out of the work in ways I can’t predict and generally don’t expect. It’s basically a long process of focused waiting.

- Try to be alert to the things my subconscious is saying to me. I’m very bad at this, even though I know most of the good stuff happens down in the subterranean layers of my brain. I don’t have direct access to any of it, so—again—I just have to wait.

I’ve thought a lot about the fickle engine of creativity in my subconscious. I picture it as a closed door, with a mail slot and no handle. Every day I try to slip new material through the slot—interesting conversations I’ve had, scraps of prose from good books, images from good movies. I get no feedback at all; there’s no sign anyone’s on the other side.

Except, sometimes, when I’m writing, the door opens a crack and something flies out. This is easy to miss: it happens so quickly and quietly that, if I’m not paying attention, I might not even notice. And by the time I do, the door’s already closed.

I look at the thing that came out from the other side. It’s usually inscrutable, presented without explanation or context. Maybe it’s an image of a cat looking out the window at an approaching storm; or a scrap of dialog between two crumbling statues; or a glimpse of a woman gently lifting a dead raccoon off the road and putting it in a box.

The trick is recognizing the thing for what it really is: a gift from the secret generative force living in my mind. A key that unlocks a story it wants to give me.

I’ll need to work for it, though. So I pick the thing up, put it on my desk, look at it for a while, and go back to writing.

That’s not a process at all! you might say. That’s just superstition. And you’d be right! There’s a reason writers evoke muses, routines, practices: We don’t really know where any of this stuff comes from. Maybe there’s a god putting ideas in our heads. Maybe they’re messages from our Buddhist non-self, speaking to our illusory self in the only way it can. Maybe they’re just sporadic electrochemical interactions in unexplored regions of our brain.

It doesn’t really matter. All I know is that there’s something behind that door giving me stories. If I believe in that utterly and without evidence, and build an infrastructure around it, and feed it faithfully, and work hard in its shadow—if I do all that, sometimes I manage to write a good story.

You might say: That just sounds like goat sacrifices to pagan gods. You’d be right about that too.

-

Cigarettes and Coffee

My new story, Cigarettes and Coffee, has just been published in the January/February 2023 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction.

… and it’s such a thrill: I’ve dreamt of being in Asimov’s for literally decades.

The story is set in the small town of Amos, in West Texas, around thirty years from now. America is in the early stages of becoming a full surveillance state, but the tendrils of the Department of Observation haven’t quite reached Amos.

That’s beginning to change. In this excerpt, a new police robot has arrived in town, and the sheriff is bringing it to the station for the first time.

Miller’s rummaging through his desk drawers when I come in with the new Gerald.

He doesn’t look up. “We got any spare phones, Sheriff?”

I hang my hat on its hook and point at an empty desk. “That’s yours.”

“What’s mine?” Miller says, and looks up. Freezes.

“Thank you,” says the bot. It moves to the desk, pulls out the chair, sits. Our Gerald — the one we’ve had for the last decade — would have just gone still until it was told to do something, but not this one. It studies the office, sliding its head left and right, up and down.

It looks real. It’s got skin and a face and short brown hair, parted to the side. It blinks. It’s got fingers, and the fingers have nails. It moves fluidly, like a dancer.

Still: there’s something off about it. You can tell.

Miller can definitely tell. “What the fuck is that?” he says.

“I have not yet been assigned a name,” it says.

“You’re New Gerald,” I say. I sit down at my desk and switch on the computer. The monitor blats awake then sizzles quietly while the drive grinds through the boot sequence. I lean back in my chair, look at Miller. “Where’s the other one?”

“Cleaning up a wreck on 90. Why do we have a new Gerald?”

“I’ve been temporarily assigned here to assist with your investigation into Observation equipment sabotage,” it says.

That’s new too. Our Gerald doesn’t say anything unless you say something to it first. Miller stares at it. We sit there, not saying anything, until the computer finishes waking up.

I squint at the litter of icons on my desktop until I find the one I’m looking for, double-click it. The drive churns for a while. It’s the old kind, read heads skittering over stacks of spinning platters. They don’t sell these things anymore, but Bel always seems to find another one when mine gives out. Probably gets them over the border, at the Bazaar in Ojinaga.

I asked her once if she could build me something faster. That set off one of her more spectacular rants. The newest solid state drives won’t work with my ancient motherboard, she said, so she’d have to find an old one that does — unlikely, given the failure profile of early SSDs — or get me a brand new motherboard. A new motherboard means new cards for all my ancient peripherals, unless she could find one with PCI slots, which is even less likely than finding a workable SSD. And no matter what she’d have to scrub everything for surveillance trapdoors, plus re-spoof the fingerprints Panop expects all its hardware to transmit back to the mothership. She paused there and looked at me, set jaw and stiletto eyes. So maybe you could just wait a couple extra seconds for fucking Solitaire to start up? Think you could manage that, Jake?

I only asked once.

-

Don't Let's Start

I remember the first time I heard They Might Be Giants. I was sixteen-ish, I think, visiting my friend Pete at his farm. There was a deck being built, I believe. It could be that I was there to help build it. But probably not.

My memory feeds me details about the past reluctantly, in a sort of staccato impressionist smear. It’s hard to pin down details.

At any rate, there was a deck being built, and I was there, and Pete was there, and my friend John was there, and John was playing TMBG’s eponymous first album.

It bewitched me. I’d never heard anything like it. Granted, my range was pretty limited back then: I grew up on a steady diet of 80’s pop music. But even from that blinkered perspective I could tell this was something special. Quirky melodies married to quirkier lyrics that weren’t just strange but mysteriously strange, and silly and clever and fun.

I’m not sure if I heard Don’t Let’s Start — the fourth track on their first album — that day, but its lyrics have been burned in my mind for the last 35 years:

When you are alone, you are the cat, you are the phone

You are an animal

The words I’m singing now

Mean nothing more than ‘meow’ to an animal

Wake up, smell the cat food in your bank account

But don’t try to stop the tail that wags the houndI don’t know what this means. Why does it make me so happy? I don’t know that either. That’s the mystery of TMBG.

Anyway, they’re still around, still making music, still touring. A few years ago they reissued their music video for Don’t Let’s Start. It’s as delightful today as it was in 1986.

-

Pride and Prejudice

The Incomparable podcast’s latest Book Club asked its hosts to pick books from four categories:

- Sci-fi/fantasy they’d recommend to non-SFF fans

- Classics that still hold up

- The best book they’d read this year

- Books they didn’t expect to like, but did

It was a great discussion, and I’ve been thinking about what I would have chosen ever since. My current list:

- Never Let Me Go (Kazuo Ishiguru)

- Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Douglas Adams, of course)

- A tie: Klara and the Sun (Ishiguri, again) and Crossroads (Jonathan Franzen)

- Sense and Sensibility (Jane Austen)

Lots to say about all of these, but the book that I settled on immediately was Sense and Sensibility.

I read it a long time ago, and have no idea why — “early 19th century novel of manners” is more or less the opposite of the sort of thing I normally enjoy. I can still remember the immense shock of loving it, though. It delighted me on the first page, and continued to delight me all the way through to the last.

I recently picked up Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and was delighted all over again. It’s amazing that something written two centuries ago can still feel so vital, fresh, and funny. I love its sharp prose, well-drawn characters, deft plotting. And the dialog! Some of the nuttier exchanges are authentically hilarious: formal to the point of absurdity, bombastically circumnavigating the point over and over again before finally settling on it, rarely saying in one word what can be said in five.

One of my favorite exchanges is between Elizabeth and the pompous Mr Collins, whose proposal Lizzy has just rejected. She tries desperately to convince him that she means it.

“I am not now to learn,” replied Mr. Collins, with a formal wave of the hand, “that it is usual with young ladies to reject the addresses of the man whom they secretly mean to accept, when he first applies for their favour; and that sometimes the refusal is repeated a second, or even a third time. I am therefore by no means discouraged by what you have just said, and shall hope to lead you to the altar ere long.”

“Upon my word, sir,” cried Elizabeth, “your hope is a rather extraordinary one after my declaration. I do assure you that I am not one of those young ladies (if such young ladies there are) who are so daring as to risk their happiness on the chance of being asked a second time. I am perfectly serious in my refusal. You could not make me happy, and I am convinced that I am the last woman in the world who could make you so. Nay, were your friend Lady Catherine to know me, I am persuaded she would find me in every respect ill qualified for the situation.”

“Were it certain that Lady Catherine would think so,” said Mr. Collins very gravely—“but I cannot imagine that her ladyship would at all disapprove of you. And you may be certain when I have the honour of seeing her again, I shall speak in the very highest terms of your modesty, economy, and other amiable qualification.”

“Indeed, Mr. Collins, all praise of me will be unnecessary. You must give me leave to judge for myself, and pay me the compliment of believing what I say. I wish you very happy and very rich, and by refusing your hand, do all in my power to prevent your being otherwise. In making me the offer, you must have satisfied the delicacy of your feelings with regard to my family, and may take possession of Longbourn estate whenever it falls, without any self-reproach. This matter may be considered, therefore, as finally settled.” And rising as she thus spoke, she would have quitted the room, had Mr. Collins not thus addressed her:

“When I do myself the honour of speaking to you next on the subject, I shall hope to receive a more favourable answer than you have now given me; though I am far from accusing you of cruelty at present, because I know it to be the established custom of your sex to reject a man on the first application, and perhaps you have even now said as much to encourage my suit as would be consistent with the true delicacy of the female character.”

“Really, Mr. Collins,” cried Elizabeth with some warmth, “you puzzle me exceedingly.”

You puzzle me exceedingly. Need to find a way to slip that into conversations.